What Makes a Good Park? Part 2

In Part One of this series on park design, I wrote about how well-planned parks fit into a city and a series of neighborhoods, such that they not only present the beauty of nature (albeit designed nature), but also useful active and passive recreational space. And, that their location & integration are keys to their success as much as their own design features. Today I’ll examine a park system that I’m intimately familiar with, and which has often been used as a hallmark example of quality park design – the parks and boulevards system in Kansas City, MO.

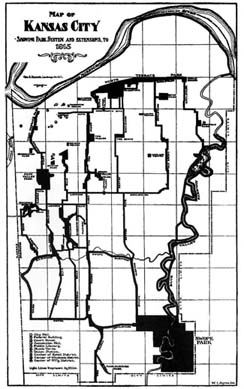

Designed by George Kessler in the late 19th/early 20th century, the parks & boulevards system is one of the most extensive in the US, and is an example of the City Beautiful approach to design. For background on the plan, look here and here. The Wilson book in particular is an excellent account of the plan, and what had to be done to get it implemented.

For the purposes of this piece, I’d like to look at how this famous system holds up to the criteria established earlier.

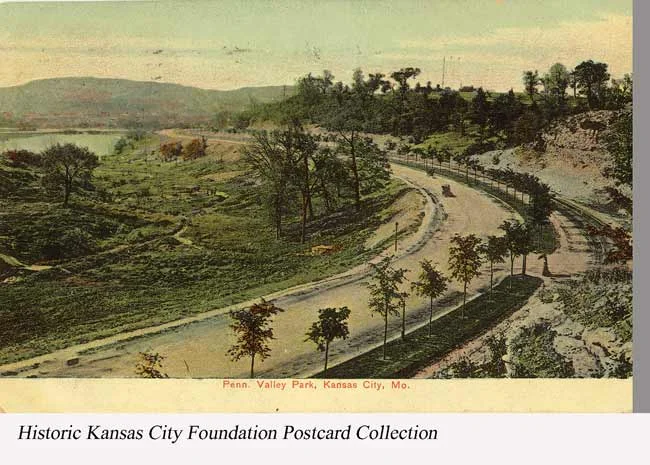

For those unfamiliar, Kansas City is not a flat city – it’s composed of gently rolling hills, a few fairly steep bluffs, and a lot of minor streams and creeks, at least historically. The Kessler plan worked with the natural features, and aligned parkways and boulevards along the waterways and ridges. It purposefully cut across the city’s fairly uniform grid of streets, re-platting entire neighborhoods in the process. Interestingly, this was a precursor for what was to come in later decades with the interstate highway system.

In Kessler’s case, the desire was to create a series of attractive parks and boulevards, to “civilize” the city and provide for the beauty of nature in the urban environment. This all sounds very laudable, especially in the context of the late 19th century city, which was often dirty and crowded, with little public space for residents. And, for the most part, the system accomplishes those goals very well – it is attractive and green, especially when riding along in a car. It makes driving through the city a much more beautiful experience than driving through parts of the city without it. And, with some thoughtful changes, the system could accommodate bicycles very well, too. It would take de-prioritizing fast auto traffic, but it would not be a terribly difficult change.

Within those observations, though, lie the problems of the system – it is designed primarily for the aesthetics of driving than for the usefulness of pedestrians or neighborhoods. In fact, the roadways often form strong edges of neighborhoods, as their width and corresponding high-speed traffic makes them hazardous to cross. As a system of parks that people actually use on a daily basis, or that encourages people to actively walk around, the system largely doesn’t work. In fact, it’s easy to cynically look at the system and say that the land given over to parkways and parks is mostly undesirable land from a development standpoint. And, that this was on purpose – it was the great compromise to get a system built, without seeming to take prime land from builders, developers and property owners as the city developed.

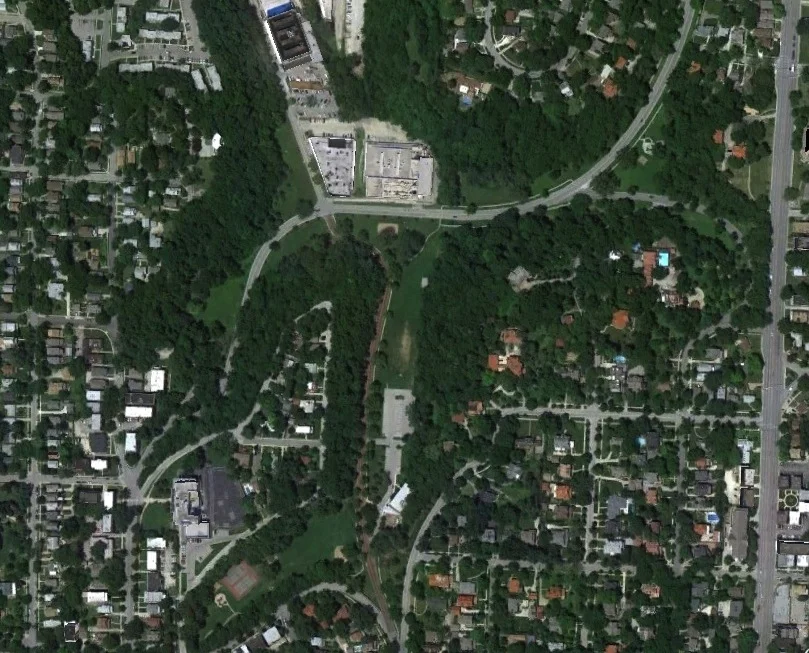

As an example of the good and bad of the plan, we can look at Roanoke Park. At over 37 acres (nearly twice the size of Forsyth Park in Savannah, and half the size of Loose Park in KC) the park is a significant part of the system. It sits amidst three Midtown neighborhoods in need of park space, since they otherwise have none.

While Roanoke does have some flat areas for fields and unprogrammed activity, and a community center, it has several inherent flaws that hinder its use:

- It sits on land well below where all the residences are – there are almost no direct eyes on the park.

- It is not on a pathway to any key destination for neighborhood residents

- It’s cut up by a series of roadways that encourage speeding

- Much of the land is physically attractive, but not usable as public space

Now, some might say – why does it matter whether the land is used or not, as long as it’s still beautiful? And, that’s true to a degree – beauty is important for life in the city, and I don’t mean to minimize it. The problem is that in cities, people need usable public space, and in particular need it as a part of their daily experience. The Kessler system, like many City Beautiful systems around the country, is indicative of a rural mindset – that wild nature should be integrated into the city in order to tame it, because cities themselves are inherently ugly. And, that nature is always superior to urbanity. In fact, these systems have more in common with State and National parks than city parks.

120 years after the Kessler plan, we now have a more refined understanding of life in cities, and have overcome the problems of the Industrial age. Our cities are much cleaner and far less crowded (the latter is not necessarily a good thing). We still have a need for larger-scale recreation, but what our cities most lack is well-designed public space,

in the places where we actually need it

. In fact, in Kansas City, MO, there are no parks or plazas at all in the actual “activity” centers – Westport, Brookside, Waldo, Country Club Plaza (Mill Creek Park is off to the side), Crossroads and even Downtown to a large degree. There are none that are along a pathway to take people to those places, except for the Trolley Track Trail, an urban rails-to-trails project. That job is left to parkways and boulevards, but they are designed almost entirely for cars.

Of course, this is not by accident. Development interests fought any inclusion of parks in the actual neighborhoods or established commercial areas of the city at the time of the Kessler Plan. Once again, short-term interests over-ruled the long-term benefits of the city.

The city does have some newer public spaces built by developers, to make up for the lack of true public spaces. Crown Center Square is a nice space, but was designed for an inward-looking development, and its own lack of a connection to Washington Square Park. The Power & Light District has its “living room” and associated pathways, which have shown the popularity and need for even quasi-public space. It’s these kinds of features the city is largely missing – places to socialize while doing other things – shopping, dining out, going to church, etc. The current park system is almost entirely about recreation, movement or quiet contemplation – the rural ideal. Very little of it is about urbanity.

My proposition is that it’s time we acknowledge the deficiencies of these City Beautiful-inspired systems (many other cities are similar), and look for ways to make targeted improvements. Why do these things? The social life of cities is what attracts people to them; it differentiates them from suburban and rural life. We spend thousands to go to far-away places and hang out in their piazzas, plazas and squares. Why not build more of them ourselves, and create that same kind of social life?

How do we do that? Stay tuned for some specific ideas in Part 3 of this series.

If you got value from this post, please consider the following:

- Sign up for my email list

- Like The Messy City Facebook Page

- Follow me on Twitter

- Invite or refer me to come speak

- Check out my urban design services page

- Tell a friend or colleague about this site