Walking, Biking, Infrastructure and Traffic Models

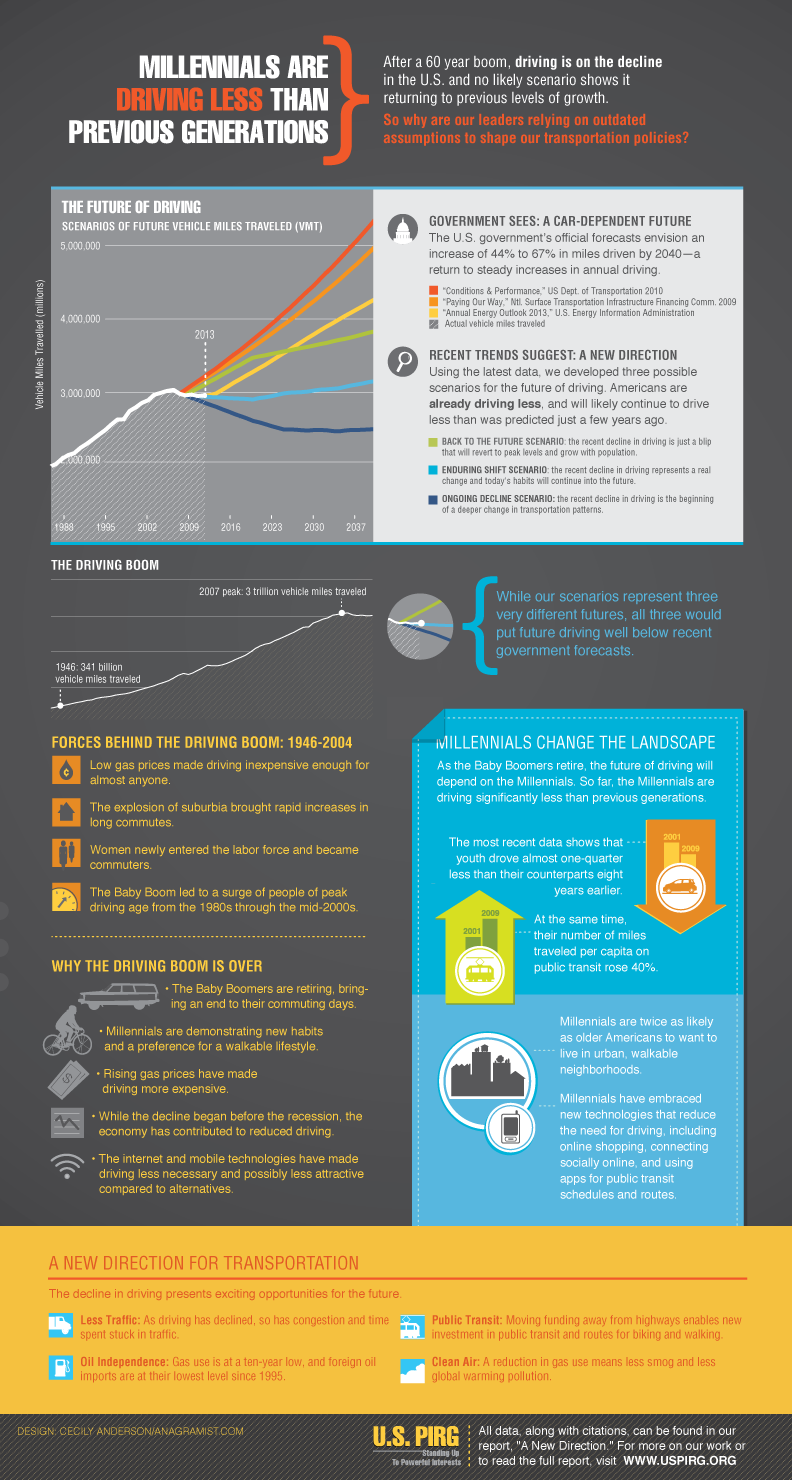

Building off of recent news about the reduction in driving, US PIRG has a new study out this week that's garnered a lot of media attention. The study, titled "Our Changing Relationship with Driving and the Implications for America’s Future" has the nifty summary stating, "The Driving Boom—a six decade-long period of steady increases in per-capita driving in the United States—is over." Here's a cool infographic US PIRG prepared:

I've written about this phenomenon a number of times, notably here and here. I think by now it's obvious that this change is real and pervasive, and more than just a blip caused by the recession. The culture shift happening manifests itself differently in every locale. Those that are already set up well for walking, biking and transit are seeing significant shifts. Those that are not well set up for it are also seeing more walkers, bikers and bus riders, but in more modest increments.

Of course the challenge we'll see as our love affair with the car culture increasingly fades is a great divergence in the ability of communities to adapt. Cities and towns that didn't slavishly accommodate cars by creating divisive roadways, giant parking lots and garages, and removing historic building fabric are already thriving with the shift. They're seeing increasingly creative ways to accommodate bikes, use every inch of valuable real estate and create the kind of community feeling that people are seeking. And, as time goes on, they will be on an accelerating course for more of the same, with new construction and redevelopment that caters to walkers and bikers.

On the other hand, those cities that did in fact make themselves dependent on cars are struggling to adapt. The auto-oriented infrastructure that we've built in so many places is extensive and expensive, and it's quite difficult to modify it at scale. Cities in this category aren't without hope, but the challenges are much larger since by nature the walking and biking experience is not as pleasant and takes up longer distances. These communities will be best served to experiment repeatedly, with numerous cheap, easy interventions to see what will work. The increasingly popular business approach of "Lean Startups" which advocates failing cheaply and quickly, with the ability to pivot to other ideas should be the hallmark of places that can't afford the big project or the big re-do. Well, that, and a focus on a solid biking network, since it's the cheapest and easiest method to encourage more contemporary living patterns.

For my money, one of the great benefits of the new data coming out is that it should put to bed the traffic modeling philosophy that we've been using for decades. That philosophy rests on the assumption that traffic will always increase, even in declining areas, and therefore we must build even more car-oriented infrastructure to accommodate it. In turn that actually induces more driving, as experience and study after study has shown, and creates a cycle that reinforces virtually all of our public money going toward roadway infrastructure. It's been apparent to those of us in the planning world for years that this paradigm was misguided at best, and certainly corruptible. Now that studies like the US PIRG effort are coming to light, it should put to death the notion that traffic will always increase, and people will always want to drive in all circumstances.

For my engineering and construction friends: this does not mean an end to the designing and building of stuff. It simply means we need to shift to what people are wanting, and believe me, there is plenty of infrastructure to be designed and built that supports it.

An example that comes to mind is when we master-planned the New Longview project in Lee's Summit, MO in 2001. A major roadway was planned through the middle of the site, which we fortunately able to redesign as a multi-way boulevard. However, the design process was fed by a traffic model that anticipated 40,000 cars a day on this road in the future. We pointed out that there were only two or three other roadways in the entire metro area that had that level of daily traffic, and both were in highly commercial areas, with millions of square feet of office and retail space. This roadway would largely be winding its way through a residential and neighborhood-oriented area.

The result: the road had to be designed for far more traffic than it will ever carry. This ultimately affects every detail of the design process, from how the intersections are handled to connections across the road to parking and more. It weakened a very good design, which in turn weakened the viability of the pedestrian-oriented town center we planned for the site.

These decisions and philosophical approaches are important, as infrastructure creates development patterns. It can either create great value through design, or reduce it just as easily. The inputs we use for those models, which are derived from general assumptions of behavior, are far more important than most laypeople realize. I'm glad the evidence is finally out there to validate those hunches many of us have had for quite some time. Welcome to the new world.

If you got value from this post, please consider the following:

- Sign up for my email list

- Like The Messy City Facebook Page

- Follow me on Twitter

- Invite or refer me to come speak

- Check out my urban design services page

- Tell a friend or colleague about this site