There’s a missing middle for commercial spaces, too

Of the many encouraging trends in recent years for cities, I’m especially heartened to see the interest in Missing Middle Housing. Dan and Karen Parolek of Opticos Design have coined a term and created an image that is catching the world of planning and development on fire. It’s long overdue, exciting, and fundamental to the future success of our cities. Years ago, often while on charrette together, the Paroleks and I used to bemoan the lack of attention to our own wonderful American history of these building types. We would often wander neighborhoods and ask each other: why aren’t people building these anymore, since they are clearly desirable and have so many benefits? In my own neighborhoods, I’ve long admired the simple small apartment buildings that have endured, and have been hopeful to one day see new iterations of the same. The examples are hiding in plain sight, all over America.

Missing Middle Housing image by Opticos Design

Dan and Karen put it very well on their website, missingmiddlehousing.com and I’d share this as an abbreviated summary of some of the key features:

They are idea for walkable neighborhoods

Buildings have a small footprint, which helps them blend with other residential buildings

They create community by virtue of design

They provide access to opportunity

Construction is simple – often wood-framed and three stories or under

Their site has a compendium of examples, and I highly recommend it if you aren’t too familiar with the term or concept. As a side note, Dan and Karen are yet another example of first-rate Gen X professionals quietly making a difference in the world.

I mention all of this because I want to elaborate on something that I wrote in a previous post. In my post comparing neighborhoods, I made the following statement:

What this means for wealth creation cannot be understated. The opportunity for a business or a small developer to own income-producing property is exponentially better in one pattern over the other. That means more local people (generally) owning property, and more local people benefiting from the economy. That’s no small matter. Stay tuned for more on this.

So, here’s the more. There’s a missing middle for commercial and non-residential buildings as well.

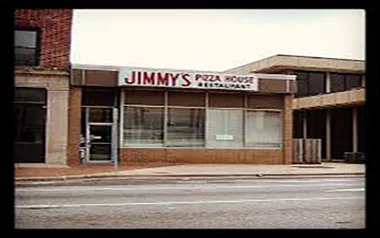

Jimmy’s Pizza image from Strong Towns

Foxy Loxy - Savannah, GA

Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns often tells the story of Jimmy’s Pizza in his presentations. The restaurant occupies a small, one-story building. Maybe you know of someplace similar in your own neighborhood or city. It screams of local character and primarily serves people that are residents of the community. In my neighborhood, I think most often of a coffee shop called Foxy Loxy. The owners took a risk and purchased the building, started a great little business and it’s become a beloved neighborhood institution. The success of this one shop ultimately has enabled the owner to start up three more local establishments, all playing off of the “fox” theme. They are great local people, owning and investing in the Savannah community, with businesses that the resident population loves.

In our urban communities, we talk a lot about local character, uniqueness and small businesses. Yet, we are often confused about what strategies might actually help to enhance that character or build upon it. Many people think it’s a problem of money; i.e., that we need to throw more money in incentives to local or small businesses. Some think it’s all the fault of a system rigged to support corporate chains. And others still think it’s the fault of government that purposefully stifles commercial enterprises.

Those all have some grains of truth, but the bigger reality is much more complicated. It relates to our whole, modern understanding of cities and development. For about 100 years, cities all over the world have implemented an entirely new ideology that runs counter to how cities developed more naturally for centuries. This stark change was made on-purpose, based in thinking of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that was responding to the shockwaves of industrialization. Part of that approach was the adoption of a model that commerce should be separated from residences, and part of it is a larger idea that cities and economies can and should be controlled from centralized agencies that are professionally managed. The latter sounds very common-sensical to us today, but it’s important to understand how radical of a shift that was, and what the actual results have been on the ground. Every choice or approach has consequences, and we tend to overlook the negative consequences to how we manage cities today.

When it comes to the idea of functional zones for cities, copious literature has described the impact of separating all commerce out from living areas. I don’t need to rehash any of that here, other than to point out the intellectual progenitors of sprawl were Le Corbusier’s Radiant City and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City. Both were incredibly radical departures from how humans had built cities for thousands of years, and both were also wrapped up in early 20th-century political ideologies. These were not incremental, organic tweaks meant to improve human settlements based on the issues of the times. They were utopian visions, meant to completely reshape human life and destroy the old ways. What’s most bizarre isn’t necessarily what they proposed, but that 100 years later, these visions are still hailed in architecture schools despite their obvious failures.

While planners, designers and critics rightly focus on the design theories and what they’ve done to cities, we often overlook how the shift in management of cities also had an enormous impact. The city planning movement of the same era ultimately is responsible for creating citizen review boards, planning commissions, and layers and layers of zoning and development regulations. As time passed, regulations and review processes got more and more complex. Look at your city’s original zoning code and compare it to today’s. The former is probably a small booklet with simple prescriptions, while the latter is often a multiple-binder document of hundreds of pages, mostly illegible to laypeople.

These combined forces have effectively created the dilemma that missing middle housing describes: with systems so complex, uncertain and expensive to navigate, the logical development response is either a single-family house (which never gets denied) or a very large apartment or mixed-use building that is bull-dogged through the system by a team of lawyers and consultants. All of the buildings in the middle were typically built by small investors, families or individuals, and in most cases the return isn’t worth the expense or risk today. Missing middle buildings may tick a lot of boxes noted by planners and architects, but it’s just too hard to get them built profitably in our modern systems. This is all without mentioning how our society has become so brainwashed as to the virtues of the single family detached house, that residents even in urban communities tend to oppose just about any project or code change that doesn’t protect single-family areas from change.

These types of buildings used to happen routinely and naturally by small investors.

We’ve created a mess. My friend Johnny Sanphilippo, the brilliant blogger at Granola Shotgun, would tell us it’s not fixable. He’d say people are going to continue to find work-arounds within the current system, often under the radar, until our overly-complex systems ultimately fail of their own weight. It’s entirely possible that Johnny is right; he’s a very adept observer of actual human life and the ways in which people adapt to broken systems.

I still hold out a modicum of hope that we can at least fix the worst of our current regulatory systems, and that places with proactive people can demonstrate another path. For those that work diligently to try and plan for a better future, we desperately need pioneers, leaders and risk-takers to create new models. Life experience tells me that Johnny is largely right. Most people fight change of any kind, and there are deeply held cultural beliefs about cities and lifestyles that aren’t going to change anytime soon. Even so, we are beginning to see some communities make broad changes to allow ADU’s (hat tip: look at Fayetteville, Arkansas), some breaking down of the notion that cities can effectively require and regulate parking, and a broader understanding of what needs to happen to allow missing middle housing.

As you think about local character and small businesses in your own community, I’d like for you to consider four points:

1. Affordability is very important for entrepreneurs and small businesses, too. It’s not just a concern for residences. The rise of co-working spaces is a contemporary work-around, but we need inexpensive spaces that businesses and individuals can own, too. Those types range from food trucks to small one-story buildings and small mixed-use buildings.

2. We create artificial scarcity through NIMBY’ism and suburban-style zoning in urban areas. We need zoning codes in certain neighborhoods that don’t just allow buildings, but encourage and expedite them.

3. Our modern-day views on urban neighborhoods & development are historically inaccurate. Commerce was almost always finely intermixed with residences, not just located on commercial corridors. And, change was baked in by-right, which enabled economic diversity and opportunity. City governments didn’t try to micro-manage every lot or building. This allowed for broader opportunity and affordability.

4. We prevent this natural change/growth at our own peril: The restrictive approach of today detracts from what makes urban neighborhoods so appealing – the local flavor and character. Because of that, it limits the value inherent in cities and urban neighborhoods and hurts local economic development and equity efforts.

Drawing of Incremental Commercial Building Types by Mike Thompson of Thompson Placemaking

Is a desire for local character your jam? If so, fight for more commercial space by-right in your neighborhood. Fight for missing middle commercial buildings. Fight for the corner bar and the corner store. In healthy cities, upscale co-exists with modest and down-scale. This includes upper and lower stories of buildings, too. Work to eliminate the worst regulations that kill small projects and small business: parking requirements, setbacks, on-site stormwater detention, density limitations, overzealous site improvements, etc.

Help your city officials understand the difference between urban and suburban neighborhoods and craft management approaches appropriate to each. Urban areas need to be much more hands-off and messy, while suburban places need to be more controlled. They reflect the desires of two very different types of people (or customers, in business lingo). When we try to control urban areas too much because of a few people that complain, we substantially limit their value, desirability and benefit to people and local governments. When we try and get too messy with suburban areas, it’s similar. These are different ecosystems that require different thinking and approaches.

Our form-based codes specifically set up standards for small commercial buildings to enable this first step in urbanization

You may intuit that I’m saying we should just let anything happen anywhere. I’m not, although an honest examination of many of more most-loved places would find that that’s much closer to how they were developed originally. I am saying, though, that we need to have an honest re-examination of the trade-offs for our approaches today. Some people cheer loudly for everything going upscale, and are proud restrictionists because it increases their own property value. That’s good for them, but it’s bad for society. For urban neighborhoods in particular, we need to break free of the suburban approach to planning and zoning that we adopted starting in the 1920’s. An approach that is much more flexible, more true to what humans want from cities and messier. Change is hard, but not changing isn’t an option.

Preventing neighborhoods from gradual change and urbanization has consequences. It prices people out of the area, and hurts business creation. That hurts local wealth. That impacts donations to the Rotary club, the sports league, and your favorite not for profit. It means people look for locations farther afield, which means more transportation issues: traffic, parking and the like. It reduces the viability of transit, which often means more public subsidy. It hurts those with the least financial resources the most, because it prevents them from getting on the first rung of the economic ladder and benefiting from an improving local economy. Protectionism is a troublesome path, for a nation or for a neighborhood. Let’s be more skeptical and more embracing of the messiness of life.

If you got value from this post, please consider the following:

- Sign up for my email list

- Like The Messy City Facebook Page

- Follow me on Twitter

- Invite or refer me to come speak

- Check out my urban design services page

- Tell a friend or colleague about this site