The Downtown Savannah 2033 Master Plan, Part 1

What it means for Savannah

Throughout the course of the last year, the lion's share of my time has been consumed by one project: the Downtown Savannah 2033 master plan. It’s been an honor to lead this effort as part of Savannah Development and Renewal Authority (SDRA), and to work closely with the hundreds of people that participated. This was the first, comprehensive effort to master plan the greater downtown Savannah area in decades, and it was a bit of Herculean effort. In addition to raising funds, executing a PR plan, collecting data and managing the project, we organized an intense public involvement effort around a week-long public design charrette and a series of open houses in the weeks afterwards. In all, over 500 people participated in some fashion, not including efforts on social media.

Link: Download the full plan here.

In the next post, I’ll write in more detail about what this plan and this process can mean for cities and towns all over the country. There were a great number of lessons learned by those of us on the team, and I’d like to share those broadly so that communities everywhere can benefit. I'll also elaborate on how this ties to the idea of "messy cities,". I’ve said this in other venues, and I’ll say it again: Savannah (while famous in the planning world) is actually much more like every city in the country than people realize. The outsized attention that the Landmark Historic District receives, which is well-earned, obscures the realities and challenges of the other 107 square miles within the city’s limits. We all have much to learn from each other.

But on to this plan, which also hopefully has meaning for Savannahians for years to come.

Why this plan and why now?

It’s no secret I and millions of others think downtown Savannah is a pretty amazing place. People want to come here, because it’s so unique in this country. In a certain sense, Savannah’s downtown will be fine, with or without our efforts. It really will. But can we step up and enhance it, in the way that generations before us did? We often talk about General Oglethorpe, for good reason, but for 150 years after he left, Savannah expanded and grew in a beautiful, unique and successful fashion. The legacy of great planning in this city did not end in the 18th century.

While Savannah has had a number of good individual plans in the downtown area over the last 15 or 20 years, there’s not been an effort to coalesce them into one, coherent vision. Big visions still matter, even if they aren’t ever fully achieved. As humans, we need positive, tangible ideals to strive towards. Our age is very cynical (and admittedly I feel it myself at times), but it’s important to continue to give hope and excitement for the future. In Savannah, we’ve needed not just better coordination and better designs, but a compelling, achievable ideal.

Do master plans solve every issue? Of course not. I’m often surprised at what people think can be achieved through these processes. In a certain sense, it’s flattering, because when people see some compelling solutions put forward, they want other issues dealt with as well. In this case, we tried to stick primarily to the planning and physical development of the city. I certainly believe the work has implications for the very human issues of affordability, access to opportunity, quality of life and much more. But I’m also well aware, as I hope most are, that complex human social issues are just that: complex. No one person nor one plan can ever “fix” them. They require people from across many disciplines working hand in hand for decades. My hope is that this plan is a step, and shows what can be accomplished in a spirit of working together. Much more is needed.

The Civic Master Plan

One other note about how this plan came together. While SDRA has been a city-funded agency for over a couple of decades, this effort was pursued from the ground up. We helped to secure funding from other organizations, and intentionally led this effort from outside of City Hall. That’s not because we or I have any distaste for local government. Quite the opposite, in fact. I like and respect a great many people working to make Savannah better from within the City of Savannah. It's extraordinarily hard work, and so much more challenging than the keyboard warriors on social media realize.

But experience has taught me that the master plans that have the longest shelf lives are always a partnership between an array of citizen-based organizations. This is because when a master plan is led solely by local government, it tends to die as soon as a political or staff change happens. As we all know, that can happen quite frequently. Citizen-based can mean nearly anything, but ideally it means a blending of the interests of residents, business groups and the not for profit sector. SDRA, led by a citizen Board of Directors, set out to do this without additional City funding or the blessing of City departments in order to do our best as a citizen-driven planning effort. Is it perfect, could we have done better? Of course. But I, for one, am exceptionally proud of the time and effort that our team put in to make this into a unique, exceptional plan. It’s always up to the community to make sure that local government implements its wishes, and this plan is no different.

A 15-Year Vision

We started this effort by looking ahead 15 years, because it aligns with the city’s tricentennial and because that’s about as far out as any master plan can reasonably look. Beyond the timeframe of approximately the next generation, it’s nearly impossible to predict what the future may hold. We asked people to think toward 2033 with these questions:

- Will people own more or fewer cars per person? What does that mean for the demand for parking?

- If young people and service industry workers can’t afford to live near downtown, where will they go? What are the implications?

- If the region continues to grow, but downtown limits its growth, where will people live and work? Is that a good thing?

- As the downtown adds people, will public space be more or less important?

- Do we think there will be more or less money available from the state and federal governments for housing, infrastructure and transportation? If it’s less, how will we pay for improvements and maintenance, and how do we create affordability?

- What is likely to be occurring with sea level rise in 15 years? Will it have an impact on our city?

We also started with some basic principles about cities and planning, such as:

- Master plans are about the future, not every problem of today. They are much like a personal financial plan, which sets a road map for the life that you hope to have. If you don't have a goal in mind, it’s difficult to make good decisions today and tomorrow. That's true even though every plan has to be rethought and modified along the way.

- A walking city is a good thing - it gives people options, it’s more affordable, it’s safer, and it creates a stronger tax base.

- Saying you’re a walking city, though, means you have to care about the details. It means understanding that people drive much faster on a 12’ wide lane than a 10’ wide lane, and that that speed kills. It means understanding that shade is very important in a hot climate, and our wonderful oak trees need a certain amount of space in order to grow and thrive.

- A growing city is a good thing, too. The challenges of a growing city are preferable to those of a declining city. This does not mean that all growth is good, nor does all development create value.

- All decisions and choices are not about you and what you want. We have to anticipate the needs of those that aren't in the room.

- Cities are always changing. It’s naieve to think that we can micro-manage change, just like in our personal lives. We have to learn how to shape it and accept it as it comes.

- Public space, when designed well and oriented towards human needs, creates value. This includes streets, our most abundant public resource.

- Cities must be economically and environmentally sustainable. Without care given to the long-term financial needs and a region’s unique environmental conditions, a city will fail its residents.

- Community-building is always a blending of design, policy and management tools. Design alone cannot fix every problem, but neither can public policy nor effective management. The three must work together.

- Innovation and technology are exciting and necessary, but it's folly to ignore time-tested principles of civic design that humans have made cities livable for centuries.

Finally, Kevin’s own personal ground rules for planning efforts and public involvement came into play:

- Be civil

- No one gets everything they want

- If you have an idea, draw it

- Disagreement is welcome, but not being disagreeable

- We are going to have an adult conversation, including some frank discussions of reality. Every choice has trade-offs, and we will talk about the trade-offs.

Since I could write literally hundreds of pages about Savannah, this plan and the community effort, (and actually the whole plan is north of 100 pages) I’ll instead defer to our language in the Executive Summary. Here’s a key passage:

The Downtown Savannah 2033 Plan illustrates the potential and the opportunities for the city’s growth and improvement. Stretching from the river to 52nd Street, and from the Truman Parkway to the Canal District, this plan is an ambitious and bold attempt to unify the greater downtown of Savannah; to accommodate the demand for urban living and to anticipate the needs of the future. It will create a new network of active transportation options and better coordinate all modes of mobility. The plan also aims to put the City on a firm fiscal foundation, so it can continue to provide world-class public space as well as improve its infrastructure. If undertaken in whole, it is estimated the Plan could provide a boost of $4 billion in real estate value, generating $41-55 million (in 2017 dollars) to the City’s bottom line.

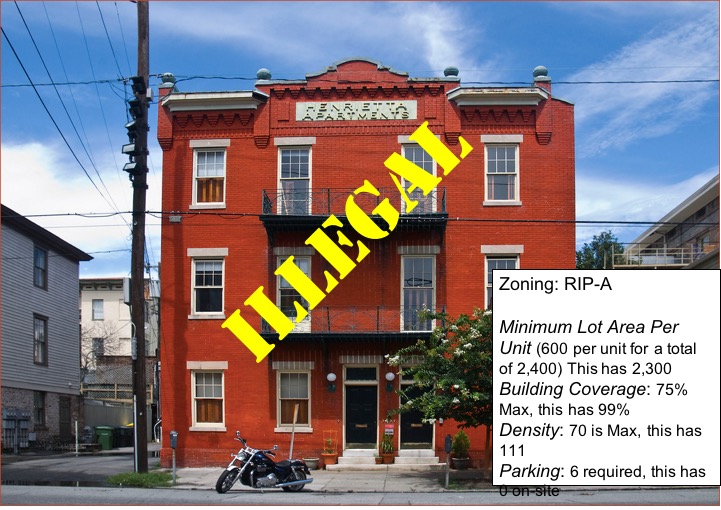

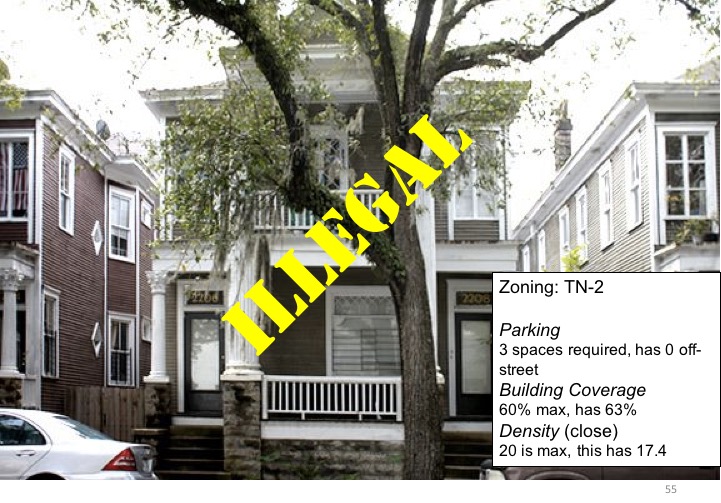

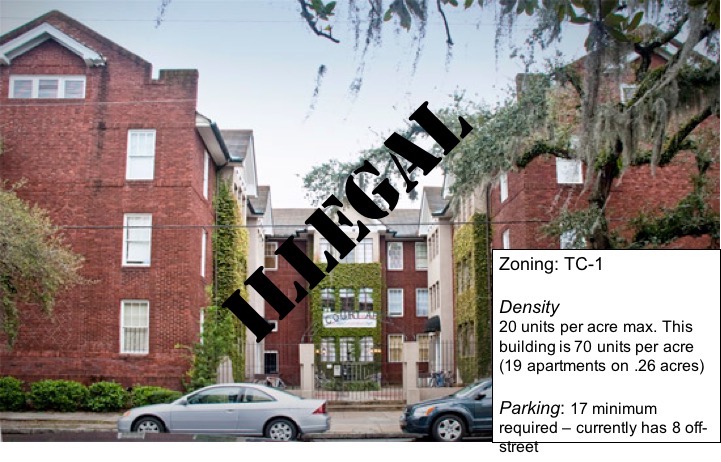

While the Plan is bold in its suggestions for public space and mobility, it is decidedly practical in its suggestions for land use and zoning. The Plan advocates to “Legalize Savannah” by altering our regulations and processes so that the common, historic building types of the city are simple and easy to develop. By removing barriers to such development, and creating streamlined processes, the Plan will encourage more of what we love about Savannah. This is not to discourage creative, unique projects, which are also necessary. But the Plan rests on a foundation on which the urban design elements that we most love should be the easiest to develop or redevelop. Savannah is remarkable not just for Mr. Oglethorpe, but for a 200-year run of exceptional city planning, design and architecture. For those of us living and working here today, what is the legacy we wish to leave? How do we enhance what was given to us by previous generations?

The 5 key priorities:

As the Plan was developed, five priorities rose to the top and became clear. Each priority is developed in depth in the full master plan document. Below is a summation.

Priority One: Expand downtown in a logical, connected fashion to the east and the west. Currently downtown is growing in a disconnected, haphazard manner with too many conflicting or uncoordinated projects. These are 300-year decisions that need to be made carefully.

Priority Two: Inject Savannah’s signature, beautiful public space design into more neighborhoods. As Savannah grew south, east and west, it often didn’t include enough public space or beautiful streets. We need to find opportunities to correct that mistake.

Priority Three: Connect it all with active transportation. Downtowns thrive when more people are walking, biking, using small vehicles or taking public transportation. Prioritizing these modes first also provides for the greatest economic opportunity for all.

Priority Four: Prioritize quality of life over commuting time. While people do commute into downtown from throughout the region, their needs should not take priority over the quality-of life needs for residents in greater downtown. Prioritizing fast commuting harms public safety and degrades the economic value of these neighborhoods.

Priority Five: Legalize Savannah’s historic building types. Our current zoning regulations make it difficult, and often impossible, to build the kinds of buildings that make up the bulk of Savannah’s historic neighborhoods. We suggest removing barriers and expediting approvals of the buildings that are the most beloved and speak to the personality of the city. Over the long term, this is a key strategy to maintain affordability throughout greater downtown, support local businesses and enhance our unique character.

The plan contains, like many plans, a checklist of what can be done, and who can lead it. It also suggests a list of short-term changes that can help towards the long-term goals. Those include some simple street network connections, bicycle infrastructure, better use of existing public-owned space, experimental projects to test public space ideas and simple changes to the zoning ordinance.

Most interesting to many is how following the Plan’s strategies can help the City of Savannah’s bottom line. This was detailed here:

The 6.7 square miles in the Plan area today contain just over $2.2 billion of assessed value (all dollars are 2017 dollars). That $2.2 billion represents 40.8% of the City of Savannah’s total assessed value of $5.4 billion. The entire City is 108.7 square miles, so essentially 6.16% of the land area generates 40.8% of the total assessed value. Of the $64.6 million in property tax revenue budgeted by the City for 2017, approximately $27.5 million is generated in the Plan area. Again, this does not also tabulate the portion of property tax that is paid to Chatham County and to the Savannah-Chatham County Public Schools.

And this:

For the purposes of this Plan, it’s instructive to estimate what a range of increase in values would mean for property tax revenues. A 50% increase over today’s valuation would represent an increase of over $14 million to the City of Savannah’s budget, annually. Essentially, that’s the equivalent of an increase of nearly 3 mills citywide.

Given the parameters laid out earlier, where certain areas could see 10-20 times their current value even at three and four stories, and especially that large portions of the Plan area are quite low in value today, 50% is on the very low end of what is possible. In fact, it’s more likely that in 2017 dollars values would be 150 200% higher if the Plan is followed. A range of 150-200% would mean an annual increase to the City’s budget of between $41 million and $55 million. Again, the total citywide property tax revenue today is approximately $64 million.

While these numbers may shock some, they are in fact quite consistent with similar studies of the value of urban neighborhoods. This analysis is not meant to demean the value of other neighborhoods in the City of Savannah, financial or otherwise. But it does reiterate three key points in the context of this Plan:

• Compact, walkable places produce a great deal of community wealth.

• Urban design has a direct impact on value, and on public revenue. Quality street and public space design enhances value, and a focus on fast commuting and ample parking degrades value. This has a direct impact on public agencies and their ability to provide services.

• For long-term fiscal sustainability, all public agencies would be wise to prioritize choices that best promote quality, compact development.

Like all master plans, this plan contains a LOT of information and work. I’d like to personally thank the team that produced it: the Board and volunteers of SDRA, our funding partners with Savannah Downtown Neighborhood Association, Ardsley Park-Chatham Crescent Neighborhood Association and the Savannah chapter of the America Institute of Architects. The design team worked exceptionally hard (volunteering a great deal of their own professional time) and worked very well together. It was led by Eric Brown of Brown Design Studio, Denise Grabowski of Symbioscity, Joe Skibba of Depiction, Dan Jarrell of Dan Jarrell Design, Jerod Rivers, Laura Ballock of Barge Design Solutions, Jim Collins of Thomas and Hutton, Charles McMillan, Gibbs Planning Group, Zimmerman-Volk Associates, Wade Walker of Alta Planning and Design and Whitney Shephard of Transport Studio. My sincere gratitude goes to each and every person involved.

You can download the full document here.

Next up: Don’t live in Savannah? I'll be writing about how the Downtown Savannah 2033 Plan could be a blueprint to your own billion dollar path to prosperity. I'll also elaborate on how this ties to the idea of "messy cities,". Stay tuned.

If you got value from this post, please consider the following:

- Sign up for my email list

- Like The Messy City Facebook Page

- Follow me on Twitter

- Invite or refer me to come speak

- Check out my urban design services page

- Tell a friend or colleague about this site