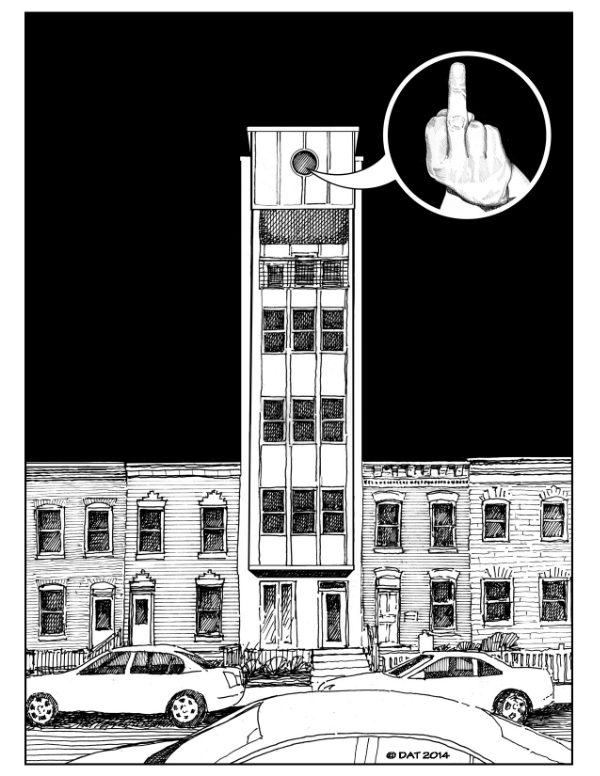

Drawing by Dhiru Thadani, architect and urbanist

Ah - the joy of neighborhood feuds that make national news. I suppose we all relish these since we likely have some similar experience. For me, it's even more interesting when it involves architecture and design. Now, my antennae are fully up.

So, it naturally caught my attention when a controversy involving a new house in Raleigh, NC made the Today show among other outlets. A short summary:

A couple's dream home has divided a North Carolina neighborhood over its design.

Architect Louis Cherry and his wife, Marsha Gordon, have drawn protests from some of their neighbors in the Oakwood neighborhood of Raleigh who say the style of the new house does not fit in. There are about 600 homes in the neighborhood, from turn-of-the-century Victorians to shotgun bungalows valued anywhere between $200,000 to several million. At issue now is whether Cherry and Gordon can be forced to tear down their two-story, two-bedroom home because of objections by neighbors.

Architecture critic Paul Goldberger even wrote a piece. Here's a snippet:

Putting aside the absurdity of revoking a building permit that was legally given, months after a building is already well under way—and the requirement that its owner needs to spend money to fight to hold onto his permit—the Cherry case says a great deal about taste, not to mention different notions of what a historic district actually is, or should be. Gail Wiesner also lives in a fairly new house, built in 2008, but hers was designed to look like a much older house. Some of the other recent houses in Oakwood are also what you could call faux-traditional, like hers, and it is clear that at least some of the residents of Oakwood envision the neighborhood as a kind of stage set, an idealized little village in which every house looks like it has been there for a long time, a place where the buildings are old and only the people, the cars, and the kitchen appliances are young.

Here's a rendering of the final design of the house, which is quite far along in construction:

Design and rendering by Louis Cherry Architecture

And here's a note from Cherry's own blog:

This article just appeared in Vanity Fair. It is unbelievable that our desire to build a modest house in Oakwood has created such a heated controversy on a national stage. I think it goes to the heart of the people's fear of change. Certainly some change can be destructive and should be resisted. This design is sympathetic to the character of Oakwood and illustrates how a contemporary design can be compatible with a historic fabric.

Now, let's get a couple of things clear right off the bat. First, the idea of suing to revoke a valid permit is something that I find absurd. The couple went through the city's stated process and received approval for their building. Anyone who objected had ample opportunity to state their objections. If the rules need to be changed, then change them. But despite my critique coming below, it's simply not fair to the this couple to pull their permit and subject them to an expensive, lengthy legal proceeding.

Secondly, it's important to acknowledge that by contemporary design standards, this house is actually pretty tame. It could very easily be something like these (just for two examples):

So, now that I've qualified my critique, let's dive into this more.

Sadly, this a complex issue made into a punch line: "backwards southern neighborhood resists change" or, "evil creative person tries to ruin a tranquil neighborhood." Take your pick. My guess is that Mr. Cherry and Ms. Gordon are very nice people, and I'd likely enjoy spending some time with them. We'd probably have much more in common than different.

But I have to admit that I sympathize with the neighbors, and I don't begrudge them for fighting for good design. Far too few people really care about these issues, which is a big reason most of our communities are not well designed to begin with.

I'm guessing (based on similar experiences) that most of the neighbors simply want a good-looking house that presents an inviting porch, looks somewhat similar to the older homes and has human-scaled features facing the street. In fact, that in most cases is all that design regulations aim for. Occasionally certain historic districts prescribe specific historic styles, but that is rare.

Sidebar: can we really still call something that invokes Prairie Style architecture "modern?" After all, the first such homes were designed and built about 115 years ago.

So, the question becomes (especially from non-architects), why can't architects take the cues I mentioned above on the public side, and get creative on the back of the lot? Why does it always have to be all modern or nothing?

Again, this is not to be necessarily negative on the architects of this home. It's a mindset and problem resident in a great deal of the profession. Architects are obsessed with being "of our time" or the zeitgeist as it's sometimes called. I wrote about this previously here. It's a mentality I wish we could evolve away from, since I personally see it as a disease slowly marginalizing architects.

There are many architects, in fact, that think they should be allowed to design whatever they want, wherever they want. Interestingly, many of those same people are politically liberal and have no issues with restraints on public behavior for numerous other societal concerns.

In the case of this house, it leads the designer to say things like:

"...it goes to the heart of the people's fear of change."

and

:...the design is sympathetic to the character of Oakwood and illustrates how a contemporary design can be compatible with a historic fabric."

Now, I agree that it could be far less sympathetic as noted above. But let's look at some features, shall we? The older houses in the neighborhood nearly all present an inviting porch/entry to the sidewalk and have a garage set back well off of the street. This house is much more inward-looking and presents a prominent two-car garage. The entry area is visually afterthought - not an inviting porch or semi-public space. It's a breezeway between the garage and the entry. The other houses in the neighborhood do far better.

Why is that important? Because neighborhoods like this create sociability. Architects too often like contemporary designs that are focused on cool interiors first and foremost, while giving less importance to how it impacts people walking by. This is an anti-social mindset that we've embraced as a profession on purpose. It's a direct consequence of architectural theory for 100+ years that the street doesn't matter, history doesn't matter, and context doesn't matter. All of that be damned; we're in a new era, let's throw out the old ways. Those old ways were far too concerned with being a good neighbor, with tradition and with time-tested approaches that restrict my creative genius. It's a short leap from that mentality to one that is explicitly anti-social.

Again, this house is by comparatively a tame example of that approach. But it's an example nonetheless. I think we can do better, and find ways to have our cake and eat it, too. There's no reason good designers can't embrace the old ways, in all locations, and still have immense creative freedom. It starts by valuing the people outside the walls as much as those inside; by acknowledging that how we behave in public is important; and by reinforcing sociability in all of our designs. That mindset can produce (and has produced) excellent contemporary and new traditional buildings. As we evolve, it would also be helpful for more architects to come to grips with the reality that the vast majority of people simply don't respond to contemporary architecture as much as fellow architects do.

In other words, it's time for us to grow up a bit as a profession, take a long look in the mirror and begin to value the wisdom of others.

If you got value from this post, please consider the following:

- Sign up for my email list

- Like The Messy City Facebook Page

- Follow me on Twitter

- Invite or refer me to come speak

- Check out my urban design services page

- Tell a friend or colleague about this site